As an artist I’m not big on sitting around and waiting for inspiration. I believe you have to develop work habits that keep you making art even when you have no inspiration. You’ll get into whatever you are making as you work on it but if you never start you’ll never get into it. So just start drawing. But you also have to find ways to inspire yourself. I did that just the other day.

I post my art on Instagram. My handle is “ArtByOsborn. I don’t have many followers and I am not an influencer but still I persist. I usually post my street photos which I make specifically for Instagram or I look through some of my paintings and drawings that I have scanned into my computer and post one of them. With the street photos I look through the vast number of street photos I have taken over the years until I find one I want to work with. Then I use my iPad to crop, color correct, or maybe even add some special effects to it before I post the photo. That’s pretty straight forward.

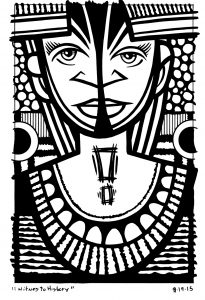

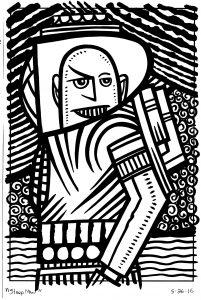

For my artwork one of the folders I look through is my folder of raw scans. There are working drawings and finished pieces in there. I scroll through the folder until something catches my eye and I post it. But as I was scrolling through the last time I came across a series of drawings that I forgot about. They’re from back in the summer of 2015. They’re ink drawing but they were made in a way different than my usual ink drawings. Usually when I make an ink drawing I take the time to figure out the drawing in pencil first. Or sometimes, for smaller drawings, I do no pencil work and go right to ink to make a spontaneous ink drawing. These drawings were not done either of those usual ways.

First off these ink drawings were done of 6×9 inch paper. My usual ones are on 2.5×3.5, 5×7, 9×12, or 11×17 inch pieces of paper. I often do pencil drawings on the 6×9 inch paper (I cut 9×12 inch paper in half) but hardly ever ink drawings. That’s because I was making these ink drawings as if they were my pencil drawings.

When I make a pencil drawing I often look through my sketchbooks (that I draw ink) to find an image I want to work with. Then I blow up that image and print it out (in blue line) on a 6×9 inch piece of paper. After that I draw over the blue line sketch and make a more refined pencil drawing. In the case of these ink drawings I didn’t pencil anything and inked over the blue line sketch to make a refined ink drawing.

One of the things I like about working in ink is the immediacy. You make a line and it’s finished. There is no erasing or covering it up. It’s dark black on white paper. So I have to think about what I’m going to do but after I start putting lines down it can move quickly. I can make a lot of images with this method and as an artist I’m a huge fan of making images.

Oddly I had a hard time getting started. The first step was easy enough as I pulled out last year’s sketch book and found about eight little drawings that I liked. I printed them out in blue line only 6×9 inch pieces of paper and was ready to go. Then I couldn’t get started. I can generally concentrate well and not get distracted by stuff but that morning I was distracted for over an hour. Every time I tried to get going I couldn’t.

I wanted to see if I could get all eight drawings done in a single day but because of my slow start I couldn’t. Each drawing ended up taking at least an hour and so I ended up doing six of them that day. At about 7PM I wanted to get started and finish the last two but I stopped myself. I had been working on them since 8AM and it was already a long day. If I was to keep going I’d probably just mess them up.

I’m a morning person. I do my best thinking and get my best work done in the morning. I never work past 9PM and these days rarely ever work that late. A couple of Sundays ago I was working on one of my masked photos and I wasn’t yet done with it. It was about 8PM and I was feeling energetic so I decided to draw the mask then and there instead of waiting until the morning. It only took me about half an hour. The next day as I was working on the photo I was having a tough time finishing it. That turned out to be because the mask I drew was terrible. I redrew it and finished the photo. I shouldn’t have bothered trying to draw it the night before because it was really too late for me to start something. You have to know your strengths and weaknesses.

I had forgotten that these ink drawings were a good way to work up a lot of images. That was my inspiration. I thought to myself that I could get a lot of these done and then I could use them to make more stuff. I’ve wanted to do more of my large 22×30 inch ink drawings but haven’t gotten started on any of them in a while. I can use these smaller ones to work out the bigger ones.

So far I’ve done two female figures, one male figure, a couple of androgynous ones, and a monster. I keep flipping through them to see which one I want to make bigger and it might be a masked androgynous one or a monster. Or maybe I’ll keep going and make some more. I’ve got inspiration and habit going for me now.