I’m not a person who feels a lot of nostalgia but every now and then it gets me in its grip. This week that was when I read an old comic that was on my pull list back in the 1980s. It is called “Night Streets.” This was the first time I read the series since then. A solid 34 years have passed since I last cracked these comics. Reading them brought me right back to 1986-1987 and put me in the head space of that time.

1986 was a unique time in comics. Because of the success of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles comic we were in the middle of what was called the “Black and White Boom” of comics. Back before desktop publishing made it easy to publish color comics small press comics were all in black and white. Except most fans didn’t like black and white comics. There were a few exceptions but in general fans were used to color comics and saw black and white ones as inferior. SO they passed them by.

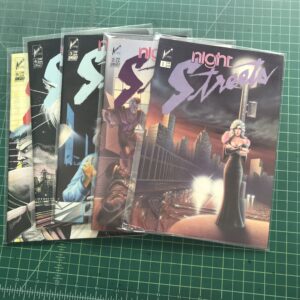

In 1986 I was twenty years old and I had already been buying black and white indie comics for a few years. They were up my alley. When the black and white boom hit I suddenly had a lot of new comics to choose from. The vast majority of them were crappy but there were some gems in there. One of the gems that I remember liking was “Night Streets” by Mark Bloodworth. it ran five issues form 1986-1987.

What made the black and white boom so unique was that suddenly anyone could get in the game, publish a comic, and hopefully find an audience. Before the boom there was very little hope of finding an audience. During the boom as a comic book creator you could be be in comic shops and a part of the comic book scene in a way that never happened before.

Nowadays you can have a successful comic book or strip on the web or through crowd funding and never be part of the comic book scene. I read webcomics every day and go to the comic shop every week and yet there are successful comics that I’ve never heard of. The scene is a lot more fragmented than it was in 1986 when you had to be on the newsstand or in comic book shops.

Kevin Eastman, Peter Laird, and their Turtles became as important to the comics scene in 1986 as anyone in a way that I don’t think can be repeated today. They got shops ordering and fans buying black and white comics in hopes of duplicating the Turtles experience both creatively and as valuable collectors items. They made black and white comics legitimate in a way they weren’t before to mainstream comic book fans. It was amazing to me at the time and now looking back too.

The first issue of “Night Streets” is dated July 1986, the second has no date (but says it’s published quarterly), the third issue January 1987, the fourth issue May 1987, and the fifth issue has a December 1987 date on it. Mark Bloodworth was doing the writing, pencilling, and inking on it so I bet that took a lot of his time. Hence the long wait between issues. I had the series on my pull list so my local comic shop would order a copy of it for me every time it came out and I didn’t miss an issue.

“Night Streets” takes place in an unnamed East Coast city in the USA. It has a huge cast of characters and chronicles a couple of crime organizations in the city. It’s mainly a cops and robbers tale with a bit of odd superhero stuff thrown in. The guy who runs one of the crime family’s is called Felonious Cat and he is indeed a giant cat who walks like a man. There is no explanation as to why he is a cat and only about half a dozen people know he exists. He doesn’t want his identity as a cat revealed and that is part of the plot.

There is also a woman who goes by the name of “The Black Dahlia” and she rides around on a motorcycle at night and fights crime sort of like Batman. She works with and is admired by the police but she’s just another character in this story and not nearly as fanciful as Batman. There is also a friend of hers who writes and draws a comic book about her. That guy is a main character in this comic.

The rest of the rather large cast of characters come from Felonious Cat’s organization, the rival criminal organization, the press, and the police. There is a lot of talking in this comic. It reads more like an episode of a TV drama than a comic book. One of the letter writers even said the only place to find more words in a comic is in an Alan Moore comic. Some people have a problem with wordy comics but I don’t. That is as long as the words are well written. They are here.

As with most black and white comics of the period the artwork is a bit rough around the edges. In this case I think it’s the inking. There are a lot of pages with a lot of panels especially in the first couple of issues. Bloodworth was using a twelve panel grid for a lot of pages especially in issues two and three. That made the nine panel grid stuff seem roomy. The inking didn’t help organize the space but instead, with all its marks and detail, made the page denser than it should have been. Sometimes it was hard for my brain to parse what I was looking at. But the art did get more clear as the series progressed.

Despite the inking problems the storytelling the art was doing was good. There was a big cast but I never had trouble telling who was who. A lot of them were drawn with extreme fashions so that helped. Over all the art was talented beginner stuff which was pretty good in context of the black and white boom. I read all five, rather long, issues on a Sunday night. So they really kept my interest.

The nostalgia part had to do with the rest of the stuff in the comic. The whole experience of reading actual comic books from 1986-1987. There were editorials, ads, and letters pages to read and I read them. I could see the people involved learning as they went. The lettering on the first issue was amateur hour. It was typeset lettering so it was readable but the balloons were terrible. In a later editorial they mentioned the first issue had a tight deadline and it shows in the lettering. It improved with the second issue.

The editorials were filled with plans and hope. They were making comics (Arrow Comics also published a couple of other books) and planning for the future. They even banded together with other small press publishers to form the “Independent Comic Publishers Association” and put that stamp on the cover. I got caught up in the big dreams all over again. The letters pages were even fun as fans wrote in with their praise and criticism. Mark Bloodworth even wrote a special response to one punk rock fan who wrote in with a complaint that the comic made punk rockers look bad.

The fifth and final issue started with an editorial about how there were big changes at Arrow Comics. Their main editor quit and got himself another job and an assistant took over. He had less of a strong editorial voice. In hindsight that was a sure sign of things falling apart. When the boss finds another job the end might be near.

The sixth issue was supposed to wrap up the story but it never came out. I’ve recently found out the Caliber Press published “Night Streets” in two collected editions in 1990, including the lost sixth issue, but I don’t have them. I’m okay with not having the last part. That’s part of the nostalgic experience of reliving the 1980s black and white boom all over again. Most everything was left incomplete.